5 Considerations for Managing a Project Portfolio

This blog is reader-supported. When you purchase something through an affiliate link on this site, I may earn some coffee money. Thanks! Learn more.

A project portfolio is all about prioritizing. Together with the common-sense notion that you can’t just pursue your main goal and leave behind all that is secondary, the main reason to use a portfolio is the assumption that no organization has enough resources to fulfill all of its goals simultaneously.

The mission of a project portfolio manager is clear enough: maximize the business benefits of projects. So is the general approach: a central administration oversees which projects are initiated, how many resources they receive and what they yield.

How to execute the approach, that’s where the devil lies.

In this article, you’ll learn the top 5 key considerations and knowledge areas under which the main criteria for managing a project portfolio can be grouped.

While there isn’t a recipe, and it would be foolish to look for one outside the context of your organization, it certainly helps to know how to recognize the potential sources of conundrums, and to set the basis for judgment.

Consideration #1: Portfolio scope should be an inspiration and a source of debate

Similarly to a project, a portfolio also has a scope. However, the relation between portfolio scope and results is exactly the opposite to those of a project.

Project scope includes all requirements in the smallest foreseeable detail. In project portfolio management, the scope is defined strictly top-down, stemming from the overarching goals as a source of inspiration into the types of project that are aligned with them and are likely to be initiated.

The scope of a project portfolio usually informs the type of projects that make up the activity of an organization.

Some of the main criteria that should be considered for the scope of your portfolio include the following.

Goals and objectives

A portfolio manager should always have a clear response to the question: What does the portfolio seek to enable? How does this project contribute to our goals and objectives? Does it contribute to more than one of them simultaneously?

Beyond the overarching goals and the main objectives, it’s recommended to also define intermediate objectives that function as enablers and success criteria.

Strategies and tactics

Strategies and tactics must be articulated: they are the practical translation of the company’s goals and strategic objectives. It’s common to bind together projects that support the same business objective into tactical programs, while I’ve often heard larger projects that contribute to different business goals informally referred to as strategic – even in the absence of an explicit portfolio management practice.

Of course, the specific composition is strictly idiosyncratic to each organization and strongly influenced by the coordinates of each industry and the skill level of the project managers.

A typical project portfolio in pharmaceuticals is made up typically of internal projects, presided by R&D, closely followed by IT and business development, while an engineering firm may have programs of external projects classified by the nature of the result delivered.

Balance of internal vs. external projects

Each organization has to make important trade-offs in terms of internal improvements versus client delivery. It’s probably one of the most complex arenas for internal negotiations between business areas and departments, and one where power dynamics can be an important barrier.

That’s precisely why it’s wise to include percentages or thresholds of investments in the portfolio scope for each of them.

Business areas affected by the projects

Imagine that one of the strategic goals of a large construction company is to outsource all of its IT systems for greater efficiency. This will obviously enormously impact the IT department, while it will probably create the need for new procurement methods and technology policies.

The resulting portfolio will shift resources away from the downscaled unit, include smaller internal governance projects with an enormous strategic priority and possibly divest funds and resources towards projects with higher ROI.

This externality can create a race to the top for project owners, stressing again the importance of portfolio management as a balancing unit.

Consideration #2: Managing complex risk is all about balance

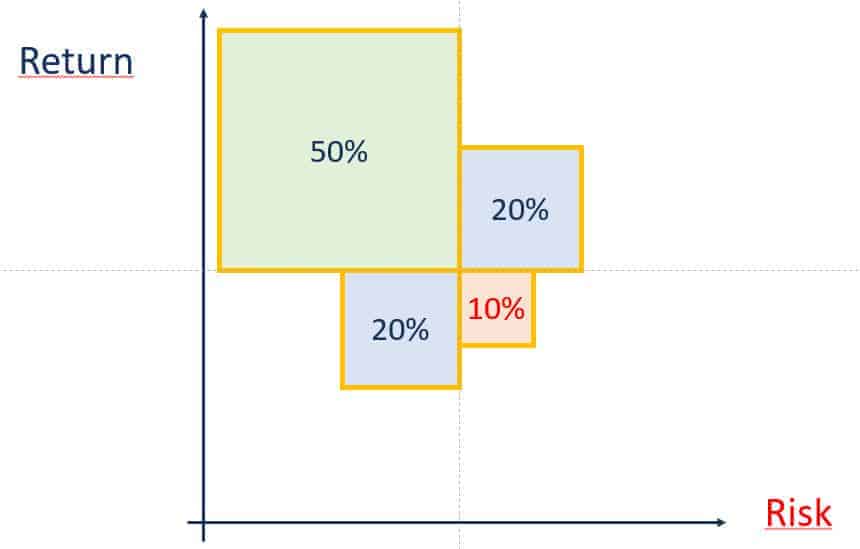

Portfolio management has a strong relationship with risk. In fact, the notion of a portfolio as a collection of disparate units (be they shares or projects) with independent results and profitability bound together by ownership is borrowed from financial theory.

In financial portfolios, the main objective is to diversify risk exposure so that in the event of loss the profits of other investments compensate the overall result.

Of course, project risks are multifaceted, extending to scope risk, technological risk and risks related to the availability of resources, to name just a few.

The diversification recipe still holds true: it’s a sound practice to have a project portfolio that combines high-risk and low risk projects.

More generally, a balanced risk portfolio would look something like this:

Consideration #3: Evaluation of project proposals is mostly about who judges them

Don’t fool yourself: regardless of the methods applied to assess project proposals, the outcome is usually very much dependent on who is on the assessment panel.

The critical moment in the administration of a project portfolio comes when a new project proposal is submitted and it has to be evaluated for approval.

While many steering committees don’t have an explicit checklist of factors for evaluation, and prefer to subject the decision to open discussion, others use an evaluation template for greater transparency with the project sponsors. In either case, a few critical aspects are always part of this discussion.

Some of them tie back to the points I’ve already made: projects need to reflect the nature of the organization, contribute to its goals and objectives, and fall within the parameters of what a reasonable project is considered. If a project proposal has no relation to the portfolio scope, it will rarely be considered.

The less governable aspect, however, is who judges, and not what is being judged or how to judge it.

Similarly to a jury, the Steering Committee ought to avoid personal biases, and the only way is to reflect the diversity of the organization: appoint female staff, as well as staff from diverse backgrounds and skill sets, age groups and minorities. If you really know the psychological profile of the candidates, it’s also a good practice to combine big risk-takers with moderates – a pattern that is actually mimicked with age and gender diversity.

The personal, soft-skilled component of portfolio evaluation is probably the most difficult to ensure with policies – but that is no excuse not to try.

There are other useful, more objective criteria. For example you can set a cap for the maximum number of projects that can be initiated at the same time, and abide by it; or not! These are guardrails your Project Management Office can define.

You can also have a policy to review it depending on whether or not you need to deliver more quickly, or whether or not you have the power to externalize more work. Some folks have even recommended the adoption of Little’s law for the administration of agile organizations.

It’s too algorithmic for my taste, but it might offer good guidance whenever there’s a concern about throughput times.

Consideration #4: Portfolio monitoring should be ongoing

Ongoing portfolio review is better than spending too much time in formal assessments.

How often do you want to shake up everybody’s routines with periodic portfolio assessments? How long will they take and how deep will they go? What are the KPIs that you will look into, and how much room will you give to qualitative analysis? How will post-mortem data feed into the larger portfolio assessments? What about potential projects, how do they get added into the mix?

These are the types of questions that you will have to find an answer for. Organizations have 6-month, 12-month and even 18-month cycles.

Whatever your choice, it cannot fall into wishful thinking: it must be realistic and take into account the following.

- The complexity of the organization

- Resource management maturity and how good your resource allocation process is

- How good your current project reporting practices are

- Whether any change requirements are likely to be followed.

If you are already collecting all or most of the data, the adoption of a proper portfolio management software will allow you to monitor your main portfolio KPIs live, greatly expediting the assessment needs.

When selecting a PPM tool, go for an option that offers value to both project managers, program managers, and the portfolio team. While many project portfolio management tools offer a great value for the latter, they may be difficult to adopt for the basic project planning needs of ‘accidental’ project managers, and perhaps add even less value to team members.

The less attractive a project management tool is for project teams, the worse the quality of project data. Which means that you should look for a tool that allows for easy project planning and execution: not just portfolio management and BI. Remember that your portfolio assessments will only be as good as your data.

Of course, you will still need to think in terms of cycles. Portfolio evaluation is different in that there is a need to monitor how objectives are being supported, and whether a shift in strategy or an environmental change is reason enough for adjustments.

Consideration #5: Include non-project work

Whenever non-project related work occupies resources that are critical to any project team, including the fixing and debugging of existing products, it can be included in the portfolio for the purpose of clarity and optimization. That level of visibility can help with capacity planning for limited resources.

Although this may seem like a secondary aspect, the improvements in efficiency of treating operational and maintenance work with a sophisticated portfolio approach can be enormous.

In other words, while for project administration portfolio managers seek to maximize goals, in the case of non-project related work they just want to get things done.

This practice can be compared to the role of

The proper administration of non-project work has the great benefit of liberating resources for other vital areas.

In a way, it’s like running the defragmentation task in your PC: as a project manager you will be capable of much more.

Managing your portfolio includes balancing these considerations carefully to ensure portfolio managers, steering committees and all project stakeholders act in the sort of loose coordination that is required to make the corporate machine work.

A version of this article first appeared in 2017.